|

By liz steinberg Tag Along Outdoor Art Raises No Eyebrows in MICA Community

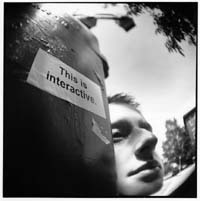

Enright is explaining the credit-card-size, silkscreened stickers he's been putting up on the back of signs around Bolton Hill and beyond--some 1,100 bearing a variety of slogans, questions, and admonitions (I AM FORCING YOU TO THINK; WHAT DOES THIS MEAN?; THIS IS INTERACTIVE). The Maryland Institute, College of Art (MICA) senior has been doing this--kind of a combination of sign posting and graffiti-tagging--since January as part of a project for two design classes, and as a sort of conceptual-art experiment.

But if Enright's artwork is less florid and attention-getting than tagging, it is, strictly speaking, just as illegal. That it has attracted little or no attention (at least formally) from the MICA administration, surrounding neighborhoods, or law enforcement says as much about the community in which it arises as does a wall covered with graffiti. In and around the college, outdoor art--sanctioned or not--is a common and more or less unquestioned occurrence. "Vandalism is really in the eye of the owner," MICA spokesperson Kim Carlin says. "A tag [or other form of graffiti] can be inoffensive if it's not offensive to the owner of the property." "I'm not offended," says Mount Royal Improvement Association President Stan Smith, a neighborhood resident with a daughter attending MICA. "I'm pleased we have the students here; they add a lot to the neighborhood." Baltimore City Police Department spokesperson Sgt. Scott Rowe--while taking care to note that "by law, people can't go around marking on things"--says police generally only investigate such activity in response to complaints, which usually develop when property has been damaged. "I'm not aware of any complaints up at the college," Rowe says. For his part, Enright says he hasn't had any problems with the law; the only people who have tried to stop him in the act are "a couple of drunks." He says he makes sure not to post on private property or obstruct signs. "If [the authorities] were really irritated with this art student's crap," he says, "they would have their priorities out of whack." That doesn't mean there hasn't been any response. Enright is documenting his work and the community's reaction at his Web site. Some folks have pasted their own statements beneath Enright's stickers; others have scrawled obscenities above them. Sometimes the response is more prosaic: "A lot of [the stickers] disappear, and a lot of them get painted over by the city," he says. Carlin says MICA's faculty "really encourages students to go out and find their own voices" through whatever means necessary, although "there isn't any encouragement for students to go out and break the law." More conventional graffiti--the kind that is considered vandalism--apparently has not been a problem. The school has "no policy" for dealing with this form of delinquency, Carlin says. (She adds, "If someone did tag the side of a [MICA] building, we would remove it.") Graffiti as artwork is nothing new. The unsanctioned installations of propagandist/artist Shepard Fairey's OBEY GIANT prints, featuring the glowering visage of the late wrestler Andre the Giant, have become fixtures in cities throughout the world since 1990, and in New York City, '70s-era tags fetch thousands of dollars at auction. It's not surprising to find something similar at one of the country's highest-ranked art schools, and the MICA community has long been tolerant of outdoor expression. Following the unexpected death of MICA literature professor Joe Cardarelli, someone scrawled HAIL CARDARELLI on a door to the campus' Fox Building in dark, dripping paint. "In other contexts, this would be considered inappropriate," Carlin says. But the Cardarelli painting "is graffiti that makes us all feel good. They just repainted the door, but they painted around the graffiti. In the context of our community, it's acceptable." It's that acceptance that Enright views as a sort of unofficial OK for

his unusual medium. "I'm in an environment," he says, "where art crimes

aren't crimes."

|

Recently in Mobtown Beat: Organization

Man Twilight

Zoning Tom

Miller

|